A cold autumn day was dawning as the German soldiers of the Altenwalde Versuchskommando prepared their V-2 rocket for launch. They’d done this a hundred times before, firing the rockets that had terrified Londoners as the Second World War dragged on. As officers and other soldiers looked on, they finished their work and watched as the V-2 finally roared up into the sky.

As the V-2 disappeared into the distance the men of the AVKO couldn’t help but smile and cheer. Their delight was catching, and soon the rest of the soldiers and officers around the launchpad were cheering as well. British officers and soldiers. Because this was Operation Backfire, the beginning of something that most people don’t even know existed – the British Space Programme.

Operation Paperclip

When most people think of the scramble for German rocketry in the chaotic final days of the War in Europe, they think of it as a two horse race between the US and the USSR. In reality though Great Britain was just as involved. Indeed arguably more than any other nation the British knew just what this new age of rocketry would usher in. For thanks to the V-2 London had become the founding member of a club whose total membership can still today be counted entirely on one hand – it remains one of the few cities in the world ever to be bombarded by ballistic missiles.

Indeed the British suffered at the hands of Operation Paperclip – America’s great quest to grab as much of Germany’s rocket industry as possible – as much the Russians did. As well as walking away with the Werner von Braun, who elected to surrender to the US (“We despised the french, feared the Russians and the British could not afford us”) the Americans walked away with the extensive blueprints and documents that he had preserved from destruction as the Nazi state collapsed. What is often forgotten, however, is that many of those blueprints and documents were in fact “liberated” from the British sector, not the Russian.

When the dust settled the British thus found themselves faced with a lack of rockets and rocket scientists. Determined to have a stake in the game, however, the British quickly realised that the men who’d been launching the V-2s on a daily basis probably knew as much about the practicalities of German rocketry as the scientists themselves. And so, Operation Backfire was born.

Operation Backfire

Prisoner camps were combed for soldiers from V-2 units and the AKVO was formed. It was a curious arrangement – the men who had launched the world’s first ballistic missile attack on London were now working with soldiers and scientists who’d often been on the receiving end of it. The photos of the Frank Micklethwaite Collection, which show British and German soldiers chatting around (and sometimes sitting on) V-2 rockets really highlight how strange a relationship it must have been.

For the British, Backfire was a huge success. Not just because it helped them gain the knowledge necessary to enter the space race but because it also left them as unchallenged masters of the of High Test Peroxide (HTP) rocketry. Von Braun was right, the British didn’t have the money or resources that the Americans had, but with HTP and a little ingenuity they were determined to compete without them.

Ultimately it was military need that drove this competition for space. With the Iron Curtain descending, Britain was keen to retain an independent Nuclear deterrent and rocketry seemed the answer – even if the grandiose efforts of the likes of Korolev (who had actually witnessed the Backfire launches) and Von Braun were out of their range.

Singing the Blues

The first real result of these British rocketry efforts was Blue Steel, a nuclear ballistic missile designed to be launched from Britain’s V Bomber squadrons. It is perhaps safe to say that it was not without issues. Working with HTP was still a new art, and it was only after the missile was commissioned that it was discovered that HTP and aircraft de-icer tended to get somewhat explosive if they came into contact.

Given that Scotland was host to more than a few V Bombers, this was not an entirely satisfactory arrangement and the Aviation Authority soon placed strict rules on Blue Steel’s operation. In fact, for a significant portion of its life this key piece of Britain’s nuclear deterrent was allowed to carry fuel or a warhead, but not both at the same time.

The first real leap forward in Britain’s space programme, however, came in 1953 with the birth of Blue Streak, a silo-launchable Medium Range Ballistic Missile (MRBM). Tested on giant gantries at RAF Spadeadam in the wooded heart of Cumbria1 Blue Streak proved to be very reliable indeed.

Evidence of the Spadeadam test site still remains at the base today, a haunting relic of a bygone age.

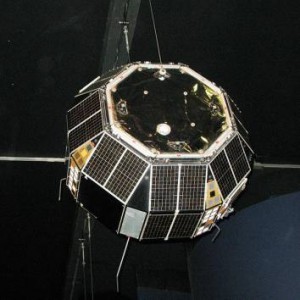

With Blue Streak looking promising, the Black Knight rocket soon followed. Designed for orbital testing and experiments rather than to carry a warhead, Black Knight was housed and tested in something straight out of a 60s Sci-Fi novel: A bunker complex looking out over the Needles on the Isle of Wight. As with Blue Streak, Black Knight proved to be a highly reliable piece of rocketry indeed.

All the key components were thus now in place for a genuine British space shot, a fact that was not lost on both the rocket manufacturers themselves and various civilian agencies. Their chance finally came in the Sixties when Blue Streak was cancelled in favour of a cheaper, “off-the-shelf,” American-built solution. Fearing a backlash from press and public over wasted cost and effort, the Government swiftly announced that Britain’s efforts would now be civilian. British rockets would put a satellite in space.

Black Arrow, Britain’s first genuine satellite launcher, based on both Blue Streak and Black Knight technology, was born.

Black Arrow

Black Arrow was a masterpiece of engineering on a budget. The project’s scientists and engineers were determined to prove that Britain could not only get into space, but could stay there. They cannibalised the knowledge and technology developed for Blue Streak and Black Knight and produced a rocket that, if launched from the right place, could put a satellite in Polar orbit. It pushed the technology to the absolute limit, but if successful laid the groundwork for a better rocket beyond – Black Prince. Black Arrow would be able to launch small satellites but Black Prince would be better. More importantly it would be the rocket that could achieve the engineering holy grail – putting payloads in geostationary orbit.

By 1968 the plans and rockets were in place, but as always money was the problem. For reasons that still cannot be adequately explained, the Treasury had taken a dislike to Britain’s rocket programme and ruthlessly trimmed its budget and questioned its expenses at every turn. This placed enormous pressure on the engineers involved. With the limited funds available only five Black Arrows could be built, and only two satellites. Working at the very edge of their knowledge and the limits of the technology they had practically no margin for error. They would, almost literally, only get one shot at their launch.

The Launch Site

That launch would happen at the joint British and Australian space town of Woomera, a strange place where both military and civilian rocket scientists lived and mixed. It hadn’t been the first choice of the British when it came to launching rockets. Indeed initially they’d hoped to launch from somewhere on mainland Britain itself, firing out over the North Sea in case anything went wrong. That plan, however, was swiftly abandoned as the North Sea oil industry began to develop and it was realised that, however small the chance was, a collision between a failed rocket and an oil rig would be a rather bad idea indeed. Luckily, Australia had all the open space that a rocket launch site could ever need and Woomera would become host to many launches of all nationalities over the coming decades.

With five rockets then, and a place from which to launch them, the Black Arrow team got to work.

The Launches

By 1969, the first of their five Black Arrow was ready to launch. As ever money was tight and worse, the Treasury had begun to review the project’s future. The Black Arrow team put this to the back of their minds, however, and in June launched the first of their precious Black Arrows.

It was not a success.

Before the launcher had even left the launchpad it developed an electrical fault. This caused a pair of the first stage combustion chambers to pivot and rotate, and it had barely left the launchpad before it began to spin out of control. Just over a minute later, as it began to fall to Earth prematurely, it was detonated for safety reasons. The only person not disappointed was the operator of range control (“I’ve never gotten to blow up a rocket before.” He sheepishly admitted as he pushed the destruct button).

All was not lost though. The reasons for the failure were found and the team prepared to try again. The second Black Arrow was prepared, with the team hoping that the launch would successfully test the first two of the Black Arrow’s three stages. This time they were more successful, and the launch passed without a hitch.

Their hopes lifted, the Black Arrow team now prepared to take a gamble. The third launch would represent the first test of Black Arrow’s third stage, known as “Waxwing.” If all went well, this would represent a genuine opportunity to put one of their two precious satellites into orbit. If it went badly, however, that satellite would be lost. With only three rockets left, however, and ominous rumours about more cuts beginning to circulate, the decision to gamble was made.

On the 2nd of September the third Black Arrow, complete with satellite, was launched. At first everything went well, but it soon became apparent that there was a problem. A leak in the second stage oxidiser pressurisation system caused it to cut out early, and although the third stage separated successfully it failed to make orbit, falling back to earth with its precious payload somewhere over the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Cancellation

Morale was low. With just two rockets and one satellite left the chances of success were getting awfully slim. Then disaster happened. On the 29th July Frederick Corfield, the Minister of State for Trade and Industry announced in the House of Commons that Britain’s independent satellite launcher programme was officially cancelled.

The quest for space was over…

…almost.

All or nothing

When news of the project’s cancellation came, the fourth Black Arrow launcher was already en route to Australia. With it was the last of the project’s satellites – a basic sound-broadcasting satellite device which had been christened “Puck.”

It would cost more, the team pointed out to the Treasury, to ship the whole lot back than it would to launch it, so why not let them have one final shot? Reluctantly the Treasury agreed. The Black Arrow team would get one last roll of the dice.

And so, on 28 October 1971, with seemingly the whole of British rocketry at Woomera watching, the countdown was started. On the pad stood the fourth Black Arrow launcher, the last with permission to fly. Perched atop its third stage sat the last of the satellites, formerly called Puck but now with a certain dark humour rechristened “Prospero” – after Shakespeare’s weary magician determined to drown his magic book and renounce magic forever.

At 3:50am GMT Black Arrow’s first stage, powered by HTP systems that the men of the AVKO would have recognised all those years ago, roared into life. Ten seconds later, on a cloud of superheated steam, Black Arrow leapt into the air. It was soon out of sight.

Three minutes later the first stage separated perfectly and, right on time, the second stage fired. The point of failure for the second stage was soon passed and right on time the third stage fired. All was going to plan!

And then, as the men in the control room watched their instruments and monitors, something went wrong. As the final stage opened up and Prospero emerged the still-moving final third stage, Waxwing, bumped sharply against it.

Silence.

In the control room no-one dared even to breathe.

They waited…

..and waited…

…and then Prospero sang.

And down on Earth, in the heart of the Australian desert, a control room full of mild-mannered British scientists and engineers cheered, and screamed, and wept with joy.

From Backfire to the Outback, on 28 October 1971 Britain joined the very small and exclusive club of countries who have independently launched a satellite. On the very same day, it also became the first (and so far only) country to officially leave it.

A Lonely end

There is no Hollywood payoff to this story. There was no reversal of Government policy, no change of heart. The final Black Arrow never flew, and you can now see her in the Science Museum in London if you know where to look. Nor did the scientists and engineers come back to a hero’s welcome. Indeed by the time many came back they had already been let go. They left as quietly as they had worked, the US space programme quietly picking up some of the best whilst others went back to industry, although none would ever forget what they had done.

But what of Prospero?

She’s still up there, orbiting the Earth. Her tape recorder broke a few years after launch, but her solar batteries still work. For many years the tracking station at RAF Lasham used to fire her up (semi-officially) on her “birthday,” but Lasham closed down twenty years ago now and a planned attempt by University College London to wake her up on her 40th birthday failed. To everyone’s dismay, it turned out that with Lasham’s closure her activation codes had been lost and they could not be recreated.

Prospero, it seems, will never sing again.

You can, however, still track her path online. So next time she passes overhead, look up and give her a little wave.

She is a last, lonely piece of Empire, in a Super-powered sky.

– or –

Great article and extremely informative. Would have liked to see a link to the National Trust who now manage the High down site and have a small free exhibition to tell the story of the IOWs part in the race for space. I believe they also manage the copyright to some of the images you have used in the above article.