Look around Endell Street in Holborn today and you could be forgiven for thinking it just an average London street. But one hundred years ago this year, this non-descript spot just off of Shaftesbury avenue was home to an important, and now near-forgotten, part of British history – the Endell Street Military Hospital, the first British Army hospital staffed, and managed, entirely by women.

Known simply as “Endell Street” by the women who worked there, the hospital played a crucial role in treating seriously wounded soldiers evacuated from the Western Front during WW1 and victims of the influenza epidemic which swept through Europe afterwards. Under the hospital motto of “deeds not words” its all-female medical staff and surgeons treated over 26,000 patients and performed some 7,000 operations before its closure in 1919. An achievement all the more remarkable given the sometimes outright hostility both they and their hospital received from many male officers within the army whose soldiers they served.

That the hospital existed at all was largely thanks to the efforts of two remarkable women – Dr Flora Murray and Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson, both of whom had already spent years fighting to be accepted in a British medical establishment that was still incredibly hostile to women.

Born in the latter half of the 19th century, both women had trained at the London School of Medicine for Women (LSMW). Now part of UCH, the medical school was established in 1874 and was the first to train women. Whether Murray and Anderson first met there is unknown, but what is clear is that at some point afterwards they became firm friends, founding a Women’s Hospital for Children together on Harrow Road in 1912. Both Murray and Garrett Anderson were also heavily involved in the women’s suffrage movement from early in their careers. This is not surprising, given their own experiences at the hands of the misogynistic British medical establishment, but it was also no doubt helped by their proximity to one of the suffrage movement’s icons – Louisa’s mother Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first Englishwoman to qualify as a physician and surgeon and Dean of the LSMW.

On the outbreak of war in 1914 both Murray and Garrett Anderson felt that they had to act – not just because they felt it was an opportunity to show what women could do, but because they believed they had a duty to put their skills to the service of those who would need them in the coming war. As Murray wrote later:

In August 1914 it was a popular idea that war was man’s business and everything and everyone else should stand aside and let men act. But there were many persons who failed to endorse this view and who held that, though men may have been responsible for the war, the business of it concerned men and women equally.

The two doctors were certainly not alone in this view, even within their own profession. Up north in Scotland another suffragist, Dr Elsie Inglis had already approached the War Office and asked for permission to raise and run a military hospital. “My good lady,” she was told, “go home and sit still!”

Whether aware of Inglis’ rebuttal or not, Murray and Garrett Anderson realised that any direct approach to the War Office would likely end in them being dismissed out of hand. So instead they decided to work round them. Casting about, they soon discovered that the French Army were desperate for medical help. On the 12th August they paid a visit to the French Embassy in London and outlined a plan to raise, equip and pay for a hospital to assist the French Army instead. Reading between the lines of Murray’s post-war account of this meeting, it is clear that the two women may have glossed over the fact that they intended the hospital to be entirely staffed by women. This omission went un-noticed, however, and equipped with letters of support from the Embassy they approached the French Red Cross who happily accepted their offer and set about securing a location for a hospital in Paris and getting them permits to travel.

Within just two weeks the Women’s Hospital Corps (WHC) had begun to take shape. Pulling on their contacts within the suffrage movement and beyond Murray and Garrett Anderson managed to raise over £2000 (about £160,000 today) and pull together the people, equipment and supplies to fully equip their hospital. Both the WHC’s name and the uniforms they designed for staff clearly demonstrated their determination to run the hospital as if it were part of British Army in all but reality. As they and their new organisation boarded the train in London to depart for the continent, the 80 year old Elizabeth Garrett Anderson watched subduedly from the platform.

“Are you not proud, Mrs Anderson?” A friend asked.

“Yes.” She answered proudly with a smile, before continuing quietly, “Twenty years younger I would have taken them myself.”

Their first hospital, established in the disused Hotel Claridge in Paris and known to everyone as “Claridges” was soon taking wounded soldiers from the British, as well as the French, army. Dealing with their wounds, often horrific, was in many cases something new for the female surgeons and staff working there, as in the pre-war world female surgeons and medical staff were often restricted (in practice if not in law) to paediatric roles. Nonetheless, under Garrett Anderson’s watch as Chief Surgeon and Murray’s capable hands as both Anaesthetist and Head of the Hospital, Claridges soon established a reputation as one of the foremost military hospitals in Paris.

Even if concerns remained in the War Office about the possible effectiveness of an organisation such as the WHC, by the Autumn they had done enough to thoroughly demonstrate to those at the sharp end that they were a more than capable medical unit. This was in no small part thanks to Murray and Garrett Anderson’s deft handling of the many military and civilian visitors the hospital attracted. Murray had insisted they use the suffragist motto “deeds not words” for the WHC and it was a course of action they actively pursued. Those deeds extended beyond just medical care, she believed, it was also about placing their obvious competence right in the face of their critics and thus leaving them no choice but to change their minds. A succession of critical Generals and administrators would pass through Claridges and each received a comprehensive tour, their questions patiently answered however insulting. More often than not they left with a higher opinion of the WHC than when they arrived.

By October, this combined medical and PR exercise had begun to bear fruit. Then, in November as fighting worsened, Murray and Garrett Anderson journeyed to Boulogne to meet a hard-pressed Lieutenant Colonel from the Army Medical Service who had previously visited Claridges and been impressed. If they moved the WHC nearer the front, they asked him, would he use them?

“Yes.” He replied. “To the fullest extent.”

They had entered his office as part of the French Red Cross, the left with papers announcing the official attachment of the Woman’s Hospital Corps to the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC).

Attachment was not full integration though, and acknowledgement of their services at the front did not automatically translate to recognition with the War Office back home. As the new hospital at Wimereux played an increasingly vital role in the treatment of the wounded though, the abilities of the WHC to effectively run and staff a military hospital became impossible to ignore. The staff made no effort to hide their suffragist leanings, but neither were they overtly promoted and more than a few soldiers found themselves discussing the cause with the hospital staff. Memorably one surgeon found herself dealing with a wounded soldier who, in civilian life, had been a police officer who had arrested her. With amusement she reminded him of that association later on the ward.

“I wouldn’t have mentioned it Miss!” He commented, embarrassed, after admitting he’d recognised her earlier as well. “We’ll let bygones be bygones.”

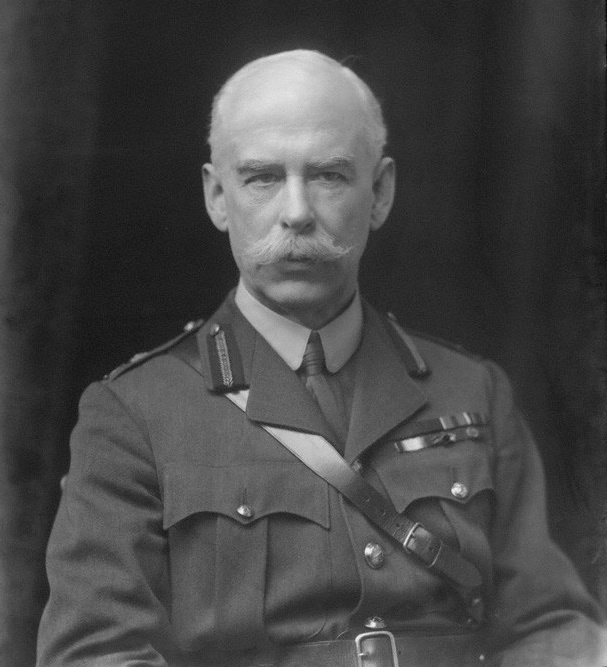

Finally, in February 1915, with the front now clearly static and an overwhelming need to open new military hospitals in England, Murray and Garrett Anderson were invited to London to meet Sir Alfred Keogh, Director General of Army Medical Services. Back home they found the bulk of the senior staff of the RAMC and the Army Medical Services still firmly opposed to the very idea of the WHC. Keogh, they discovered though, was not one of them. He had read the reports on the WHC and the recommendations coming out of the RAMC officers actually on the scene in France, he told them. Then he offered the two doctors the chance to make history – he asked them to establish an RAMC military hospital of at least 500 beds at Endell Street in London, to be managed and staffed by women and run as they saw fit.

Murray, ever modest, would later claim that Keogh deserved perhaps as much recognition for their achievement as she and Garrett Anderson did. This is not true. Without the efforts of Murray and Garrett Anderson, who built a first class medical organisation in the face of constant hardship, Keogh would have had no ammo with which to shoot this particular medical boundary down. What is true, however, is that Keogh recognised that ability was not restricted by gender and was prepared to risk his own position so that the women of the WHC could prove it.

Keogh also realised the importance of backing women doctors in public, not just in private. As Murray and Garrett Anderson set about the task of moving their operation back home, on the 18th February at a public meeting Sir Keogh publicly advocated the expansion of the LSMW (where both doctors had trained), explicitly highlighted the work of Murray and Garrett Anderson in France and informed those present, including journalists, as to what he had asked of them.

“He had asked them to take charge of a hospital of 500 beds.” The Times reported with some astonishment the next day. “And if they pleased, of a hospital with 1000 beds.”

Setting up the hospital at Endell Street was a whole new challenge for the women of the WHC. Although Keogh’s support helped, it became clear that to a certain extent they would have to fight the same battles they had fought for recognition in France all over again as to begin with the army medical establishment was once again almost actively hostile to their efforts. The location chosen for the hospital was an old Work House and getting it ready in time required significant work. The RAMC detachment working for them showed no interest in fulfilling their duty, however, and equipment and supplies also failed to materialise. In the end, the women had to appeal directly to the Director over the heads of regional command in order to get things moving. Once his wrath had descended and his patronage of them been made explicit the situation improved, but it was a close run thing. Somehow they had the hospital ready in time, only to receive as their first patients a selection of tough cases and malcontents from the other hospitals in the London region.

The general expectation amongst those opposed to their work was that the Endell Street experiment would fail within 6 months. Under Murray’s capable supervision and thanks to the efforts of all of its staff it instead quickly became one of the foremost military hospitals in London. With this the hostility gradually began to decrease, replaced with a sort of lukewarm tolerance and gentle neglect.

Indeed over time the staff would turn this situation to something of an advantage. It allowed them to ignore certain standard British Army practices in favour of new ideas. Murray was committed to the principle that psychological wellbeing was as important as physical when it came to recovery, for example, and with its bright atmosphere and focus on activities and entertainment Endell Street would come to lead the way in this aspect of patient care. Garrett Anderson meanwhile, along with a brilliant pathologist called Helen Chambers, was able to carry out extensive clinical research into the treatment of wounds and publish the results. Together they trialled, then deployed a new compound “Bipp” paste that dramatically reduced the frequency with which surgical dressings needed to be changed.

As in France the policy of “deeds not words” gradually began to change minds. The quality of care delivered at Endell Street and the development of Bipp paste made their achievements impossible to ignore. In January 1917 Queen Alexandra visited. Later that year both Murray and Garrett Anderson were awarded the C.B.E for their war work.

“I knew you could do it.” Keogh confided to Garrett Anderson with a smile shortly after ordering Bipp deployed to all forward hospitals in France. “We were watched, but you have silenced all critics.”

Keogh’s praise went further on his departure from the War Office in 1918. To Garrett Anderson he wrote:

I was subjected to great pressure adverse to your movement when we started to establish your Hospital, but I had every confidence that the new idea would justify itself, as it has abundantly done. Let me, therefore, thank you and Doctor Flora Murray – not only for what you have done for the country, but for what you have done for me personally. I should have been an object of scorn and ridicule if you had failed

By that time their success was there for all to see. Endell Street had expanded, and before war’s end even acquired three auxiliary hospitals (Byculla, Dollis Hill House and Holly Park). When the Representation of the People Act finally passed Parliament in 1918 granting the first limited voting rights to women, Murray ordered their only ever overt political act – the black flag of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was hoisted in the hospital courtyard, to the cheers of staff and patients alike.

Endell Street Military Hospital finally closed in 1919. To say that it changed things instantly would be an overstatement. To the end, despite its success, its staff still battled prejudice within the army. Although given the title “Doctor-In-Charge”, a rank equivalent to a Lieutenant –Colonel, Murray was never officially given that direct military rank itself. To the end of the war and beyond she would fight for her women to get everything they they were due as part of the Army – the pay, benefits and most importantly recognition of equality that would connote. Murray realised early on that Endell Street was a military hospital – and that the “military” part was important. When in later years the Imperial War Museum asked to include Endell Street in their “women’s war work” collection Murray refused. To do so, she pointed out, would suggest that they were a volunteer hospital during the war – those hospitals had undoubtedly done good work, she insisted, but inclusion would rob Endell Street of recognition for breaking through and being a professional, army operation. It was a subtle difference, she admitted, but one they had battled so hard to get.

So what happened next?

Some of the women at Endell Street moved on to great things. After the war pathologist Helen Chambers went on to a successful career in cancer research. One of the younger members of staff there, Hazel Cuthbert, became the first female physician appointed at the Royal Free. Many more graduates of Endell Street however found their careers limited by prejudice – despite the enormity of their experience with war wounded, for example, none of the female surgeons from Endell Street would perform major surgery again.

Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson meanwhile returned together to the small children’s hospital they had founded on the Harrow Road. Both remained active in politics until the ends of their lives, although for Murray that sadly came too soon, dying in 1923 aged just 54. Louisa survived her for another twenty years, dying aged 70 in 1943. Neither woman ever married, and they are buried together near the home they shared in Penn, Buckingshire. The inscription on their shared tombstone reads “We have been gloriously happy.”

On Endell Street itself, little evidence of their achievement remains. The old building that contained the hospital is long gone – replaced by Dudley Court, a red brick housing block. Look around a bit though and you’ll find a blue plaque marking the spot where it stood. It is worth hunting out – a few words to commemorate some awfully mighty deeds.